Books on My Nightstand Scott Silsbe

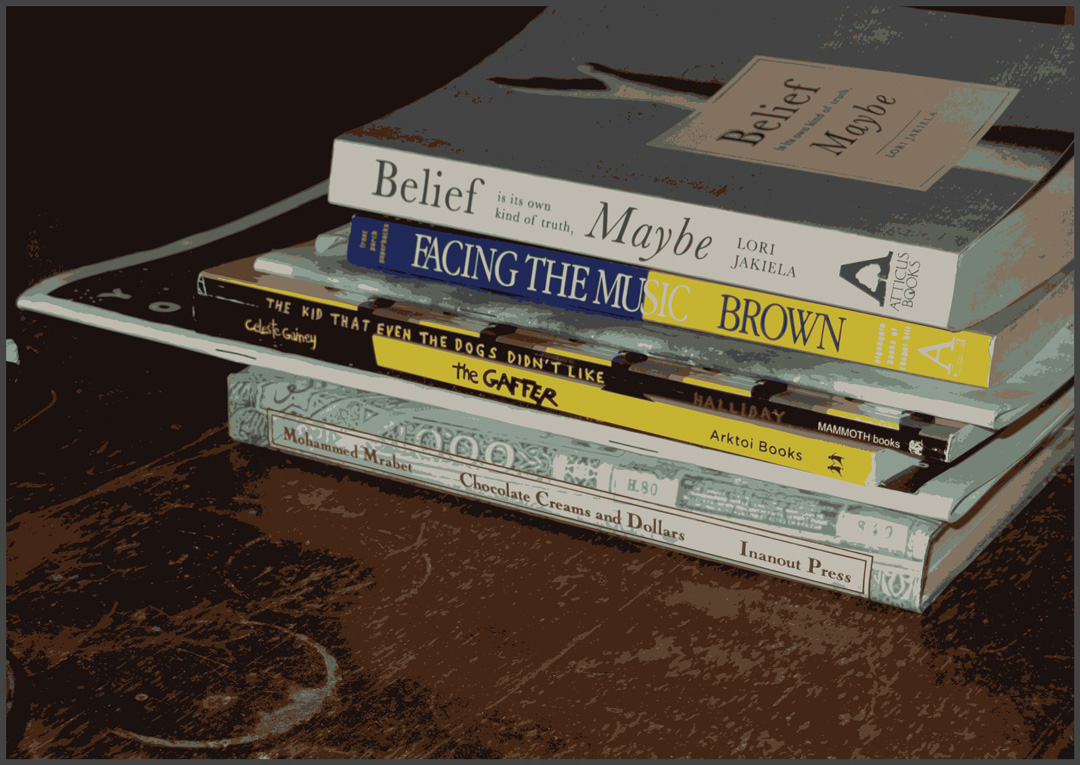

The Stack:

Belief Is Its Own Kind of Truth, Maybe by Lori Jakiela

The Kid That Even the Dogs Didn’t Like by Ray Halliday

You Can Did It, Chapter 1 by Nils Balls & Mike Carretta

The Gaffer by Celeste Gainey

Chocolate Creams and Dollars by Mohammed Mrabet (trans. Paul Bowles)

Little

As Living by Meghan Tutolo

Facing the Music by Larry Brown

A great number of books pass before

my eyes and through my hands on a daily basis. Working for a used bookstore (primarily

in that bookstore’s large book warehouse) and trying to be a ravenous reader

when I’m not at work means I’ve always got books around me. One of my early

creative writing teachers advised me that one key to being a good writer is to

read voraciously and I took that idea to heart. Piles of books crowd my

bedroom. On my dresser, on the floor by the bed, on my nightstand.

I consider it sort of a bad habit,

but I don’t always commit to one book at a time. I really enjoy constantly

sampling from different books and different types of books: nonfiction, short

stories, comics, poetry, novels. It might just be that I don’t want to miss

anything, I want to check out as much as I can. Even if that means some books

remain with a blank piece of memo pad paper sticking out of them part-way

through for months on end.

What follows are some notes on the

stack of books currently holding down my nightstand.

*

I’m making my way, for the second

time now, through Lori Jakiela’s new memoir Belief Is Its Own Kind of Truth, Maybe [Atticus Books, 2015]. The first time I read it, I wanted to read it for sheer

pleasure, just enjoy the great gift for storytelling that Jakiela has. And it was a great first read—an utter delight. But I wanted to give it a

second read through to think about it critically, so I could try to articulate

why I think it’s a great book, why it’s a book that I love.

This is Jakiela’s third memoir. It’s about adoption. But it’s about a lot more than just

adoption. It’s about the connections that we all make in this life. About what

family means and about why family means what it means. It’s about the strange

and beautiful world that we live and love in. This is an important book to me

because it says important things about life, about the hardships of life, and

about the things that we face as who we are. As human beings. And it says all

of those things in gorgeous, well-crafted prose. Jakiela is a poet and her poetry is here in this prose. The first line is already a

breath-taker: “When my real mother dies, I go looking for another one.”

I love this book because it’s not

only smart and brave and well-written—it’s also funny. Jakiela has a great sense of humor, even with difficult subject matter. Maybe

especially with difficult subject matter. Maybe because she knows that’s when

we need it most. But like the high school version of Jakiela in Belief... who busses to downtown

Pittsburgh to take a dip in the fountain at The Point, Jakiela comes across as full of wonder at the world around her. Sure, a little bit

anxious about how fragile our lives are, but only because she realizes the

richness of life. This book is invested in this world. The real world around

us. The one each of us has been living in since the day we were born. There are

references to Andre the Giant and Star

Wars and Jeopardy. And it’s all

very magical, it’s all very poignant, it’s all very real. Jakiela puts Pittsburgh on the page and it looks as magical as it is in real life. She

captures the world around us in her book and it’s just as funny and difficult

and wonderful as this life can be. I can’t recommend it enough.

*

When I was an undergrad and budding

poet back in the 90s, my most influential poetry teacher (and also personal

hero) was a guy named John Rybicki. There was a while

where John was a regular contributor to the lit mag The Quarterly. When I learned this back

in the day, I started keeping an eye out for old issues of The Quarterly at John King Books in Detroit and at other

bookstores. And once I started finding those and reading them, I became a fan

of other Quarterly contributors: Jack

Gilbert, Rick Bass, Thomas Lynch, Amy Hempel, Barry

Hannah. Another Quarterly regular was

Ray Halliday.

A couple years back, Mammoth Books

released Halliday’s The Kid That Even the Dogs Didn’t Like, a collection of short

pieces (mostly prose), including some 13 pieces that were originally printed in The Quarterly. I like that this book

isn’t easy to classify. I like that there are a couple of poems floating in

amongst the prose pieces. And I like that the prose pieces are that in-between

genre that some people call prose poems, some people call short shorts, and

some people just call short stories. There’s a nice variation of style in the

pieces too. The book starts out with “Chunk of Ice,” a shorty that reminds me of the off-beat and often odd fables of Russell Edson. A couple of pieces later is “Fourth,” which has a

really conversational tone that reminds me of Gordon Lish.

Maybe I’ve just got that association since Lish was

the editor of The Quarterly though.

Even though I said those things

about him reminding me of Edson and Lish, there is also something very fresh about Halliday’s writing. When I read this book, I have the sense

I’m witnessing a new voice with a unique vision. I find the pieces to be very

humorous, but in a way that I’m not always used to. The narrators and

protagonists in these pieces often feel awkward or at odds with the world

around them. They are in the world, but they feel like they are not really of

it. Some of the humor is in watching them interact with those around them. But

a lot of what is really remarkable to me is the interior perspective and

interior monologues of these characters. Halliday strikingly

captures the daily inner life of bumbling, self-conscious weirdos like you and me and does so in a way that entertains and delights. The Kid… is a keeper. It’s a charming

and intricately-designed collection whose subtleties and nuances will reward

multiple readings. I expect to read and reread this book for months and years

to come.

*

It’s pretty hard not to be a fan of

Nils Balls’s comics. They’re just so much fun! I was

really excited to recently get a copy of chapter 1 of the Balls/Mike Carretta collaborative self-released comic You Can Did It [2014] and I’m happy to

say it did not disappoint. I read it not too long ago and I’ve been keeping it

on my nightstand, thinking I’ll want to flip through it again when Chapter 2

comes out to refresh my memory of the storyline.

I’ll try to tell about some of the

great things about You Can Did It,

but try to save some of the good stuff in case you, dear reader, get a chance

to read it yourself. The story is set in Pittsburgh. And it does an excellent

job of really capturing Pittsburgh on the page. But it’s not just that Balls

& Carretta use Pittsburgh slang in the dialogue.

They’re somehow able to depict what it feels like to be in a Pittsburgh dive.

The Buccos on the TV, someone starting up the

jukebox, people popping in and out of each others’ conversations. The story is

centered around beer. Homebrew. A very special homebrew beer. I bet people that

don’t care for beer would appreciate this comic. But if you’re a beer-drinker,

this comic is especially fun.

I’m really impressed with the

storytelling so far. In just over 20 pages, Balls & Carretta have created several very distinct characters and I already feel invested in

their lives, I find myself curious about what’s going to happen to them. And

the artwork is stunning! Like the Jakiela memoir,

this comic shows off Pittsburgh in all of its magical glory. I can dig a

crudely-drawn comic, like say Jeffrey Brown’s Clumsy, but a comic with such craftsmanship to the drawings like

this one has really enhances the experience.

One final note . . . I love how

generous Nils Balls’s work always seems to be. It

feels to me like he’s always cramming as much goodness as he can into his

projects, coming up with as many inventive ways as he can to make a comic

enjoyable. So, in addition to the main story of You Can Did It, chapter 1 also has a mixer-sixer list of beers to drink and songs to spin to accompany your reading. And at the

back there are a few short “Bonus Beer Comics”—little one- or two-strip deals

like the kind you might find Balls doing for The Northside Chronicle or a Mellinger’s Beer Distributor ad. See what I mean? So much fun!

Looking forward to chapter 2!

*

There’s this quaint, new cafe called

The Staghorn tucked away on Greenfield Avenue in

Pittsburgh’s Greenfield neighborhood. I saw local poet Celeste Gainey read there not too long ago, and, man, did she ever

give a great reading. The poems were all from her recently released full-length

collection The Gaffer [Arktoi Books, 2015] and after the reading, I got my own

copy of the book to take home.

The poems of The Gaffer pop and jump off the page with an eloquence and style

reminiscent at times of that great 20th century master, Frank O’Hara.

And like O’Hara’s poems, these poems have a lot of New York City in them

(though there are some L.A. poems, too). According to her bio, Gainey was the first woman admitted to the International

Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees as a gaffer. And I’m pretty sure she’s

got to be the first female gaffer to write work poems. In addition to lighting

films, Gainey has spent years as an architectural

lighting designer.

A lot of the poems in here are

inspired by film—primarily Gainey’s personal

experiences as a gaffer. I don’t always like to conflate a poem’s speaker with

the poem’s author, but these feel highly autobiographical. There’s a glossary

of terms at the back for those of us unfamiliar with gaffer lingo. I appreciate

that being there, but I also really enjoy the music and mystery of the gaffer

jargon in Gainey’s poems—being swept up in the

unknown of those terms.

In addition to the poems with

entertaining anecdotes about Dog Day

Afternoon and Taxi Driver (to

name a couple), there are some really personal and brutally honest poems about sexuality

and sexism. The ones I find really compelling are the poems that bring that

subject matter together with the film-related material. Gainey is very candid about her sexuality and very outspoken about the sexism she

experienced in her years as a gaffer. Here’s a short poem in its entirety, as

an example:

cameramen

some

will leave you alone

some

will tell you where to plug it in

some

will respect you

some

will only talk sports

some

will call you baby legs

some

will not know how to talk to you

not

even hello

Minimal, but direct. Gainey has a strong voice and it feels like she pulls off

some magic tricks in this book. I like that she can take the act of buying a

pair of second-hand jeans and turn it into a transcendent moment. In some ways,

this is a poetry collection like I’ve never seen before. It delicately combines Gainey’s very unique view of the world of film from

her vantage point with her inner and outward struggles and with her wise observations

of the greater world around her.

*

My buddy Dave hipped me to Mohammed Mrabet a while ago and I’ve since become a big fan. I can’t

get enough. I think I’ve collected just about all of Mrabet’s books and I’ve read over half of them. I like his novels best—Love with a Few Hairs, The Lemon—but his autobiography Look & Move On was also great. As

far as I can tell all of his books were translated by Paul Bowles, starting

with Love with a Few Hairs in 1967. I

believe that Bowles and/or Mrabet taped Mrabet telling stories in his native Moghrebi and then Bowles set to translating them in English.

I just cracked Chocolate Creams and Dollars [Inanout Press, 1992]. This is a late Mrabet novel, but, to my

eye, it’s not a whole lot different stylistically from his early work. Like

other Mrabet novels, this book is set in Mrabet’s native Morocco and the protagonist—who is named Driss in this book—is a young Moroccan who has grown weary

of fishing for a living and is able to make ends meet a lot more comfortably as

a servant of sorts for ex-pats.

Like other Mrabet novels I’ve read, the storytelling in Chocolate

Creams... is very simple. The language isn’t very flowery. But Mrabet certainly knows how to spin a tale. There are some tropes

I recognize from his other books, some devices employed to keep the reader

sucked in. First of all, in most of the Mrabet that I’ve

read, there’s a good amount of kif smoking. This

always seems to lead to unexpected adventures in the lives of Mrabet’s protagonists, whether in real life or only in

their kif-addled heads. Mrabet books also usually have a love story of some sort, or at least a series of

romantic encounters. Oftentimes, this involves a sex scene or two, but usually

handled with a fair amount of modesty. Finally, Mrabet’s protagonists are typically forced to deal with someone they consider to be insane.

These people are often Americans or Brits, and occasionally fellow Moroccans.

Sometimes they are one of the women from the romantic encounters. Sometimes

dealing with the crazy person results in some kind of violence. Employing that

violence, or ultra-violence perhaps, is one of the things Mrabet is a master at.

All of those tropes are present in Chocolate Creams..., but there’s much

more to it as well. Some of the Mrabet I’ve checked

out reads more like parables or Moroccan folk tales, and I don’t enjoy those as

much as this stuff that feels very rooted in the real world. My buddy Dave

laments the fact that Mrabet books have fallen out of

print, but you can still find them if you seek them out. Maybe someday, like

Dave says, someone will come along and find them, reprint them, and make a

small fortune.

*

I love a small press poetry chapbook.

Especially one by an aspiring, young poet. Meghan Tutolo’s Little as Living [Dancing Girl Press,

2014] is just that and it’s a very impressive little collection as well. Tutolo shows off her keen ear for the musicality of

language (read these poems aloud!) and reminds me repeatedly that poetry can do

a great number of things and in different ways. She reminds me that an

essential part of poetry is the finding of form for subject and that the two

things inform each other.

I consider the poems in this

collection largely to be lyric poetry. By that, I mean a couple of different

things. For one, they are not always concerned with telling the reader a story

in a sequential way. Rather, they use a very musical language to give an

emotional charge to the reader. I’ve heard it said that when you read lyric

poetry, it’s as if you are overhearing poets talking to themselves. I see that

in some of these Tutolo poems. They are very personal

poems. One way this manifests itself is that there are a good number of poems

written in the second person. The poems can be fragmented or a little bit

static at times. But it feels like they are working through language to find

exactly what it is they want to say, to struggle with words to articulate what

needs to be said and find the right way to say it.

Outer space pops up a lot in these poems.

Moons, stars, constellations, planets, universes. There are these large,

astronomical metaphors throughout. They seem to mimic the large things the poet

is feeling, as if the only way to explain what’s going on inside her is to go

big, go biggest. There’s an underlying feeling of grief, of loss, of mourning

in many of these poems. And I keep seeing occurrences of distance in one way or

another. People being separated from each other by one thing or another. Though

sometimes they are attached by something as small as a telephone. The phrase “thinking

too much” is used multiple times. Which got me thinking, maybe that’s what

these poems are all about. Maybe that’s what all poetry is really about. Just

thinking too much, fixating in some way, but creating something out of that

fixation. Making a small universe on the page with that extra material floating

around in our heads. Getting something out of it. Something valuable and

rewarding. That’s what it feels like Tutolo’s doing.

And I’m grateful for it. I’m grateful for her universe.

*

I picked up Larry Brown’s first

collection of short stories, Facing the

Music (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1988), right after I finished

reading his second collection of stories, Big

Bad Love. Big Bad Love was a

terrific read, one of those books that you don’t want to end, so I when I was

done with it, I went hunting for more of Brown’s short fiction and ripped

through the first five stories of Facing

the Music. The book starts off with the title story and it’s a good one.

The first line is: “I cut my eyes sideways because I know what’s coming.”

Pretty great line.

The next couple of stories weren’t

great, but still, since I’ve become a Brown fan, worth reading through. I found

it distracting that the second story, “Kubuku Rides,”

used Southern dialect to tell the narrative. “Old Frank and Jesus” was a good

one. And then there was “Boy and Dog.” “Boy and Dog” is great. It looks like a

poem, but I don’t think Brown thought of it as a poem. My buddy Dave who turned

me on to Mrabet also loaned me a documentary on Larry

Brown since he knew I was on a Larry Brown kick, and there was a cool dramatization

of “Boy and Dog” in it. And there was an interview segment with Brown about

“Boy and Dog” that was really interesting. Larry Brown was a firefighter in

Oxford, Mississippi for about 17 years. In the documentary he said “Boy and

Dog” was the only story he ever wrote with firefighters fighting a fire in it.

Not too far from my nightstand is a

copy of the biker magazine Easyriders from June 1982. It’s an incredible document. Unbelievably

entertaining. Even the ads are entertaining. I never owned a biker magazine

before I owned this issue of Easyriders. The reason I got this is because I’m pretty

certain it has Larry Brown’s first magazine publication. A story called “Plant Growin’ Problems.” As far as I understand it, Brown was

trying to get into academic lit mags and got

rejection slip after rejection slip. Then he submitted to Easyriders. “Plant Growin’ Problems” never got collected in any of Brown’s

story collections. It kind of reads as if he wrote it knowing he was going to

send it to Easyriders.

But it’s a good story, it’s a really fun read.

For some reason, I set Facing the Music down after reading “Boy

and Dog.” I picked up Mrabet’s Chocolate Creams... and Jakiela’s Belief... and some other things that

didn’t even make it to my nightstand. It’s a shame because I really want to

finish it and check out some of Brown’s novels. Maybe I’ll get back to it when

I take a little vacation from the bookstore. I certainly have enough other books

stacked up on my dresser waiting to make the leap over to my nightstand.

Scott Silsbe is a poet and bookseller living in Pittsburgh.

He also likes to write songs and make noise with the guitar.