Saving Lives and Property, One Paragraph at

a Time Stephanie Brea

My first job out of college, I wrote

about inventions. It wasn’t quite as glamorous as working in a New York City

publishing house, or acceptance to grad school in Iowa, but I could say that I

was writing for a living (albeit meager). I moved back to Western Pennsylvania

after a brief try at making it in New York City. The Sinatra song says if you

can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere, except I couldn’t. After two

years, I was tired, lonely and cranky. I wanted to be where I could pay my

bills, where driving across a bridge didn’t require money, where I could afford

to eat and drink, not eat or drink.

I never thought about the invention

industry before, but my 9-5 was instantly transformed. I was drowning in

something similar to what the cable company deems paid programming. There was

new lingo to learn, and the realization that there is a whole segment of the

population that I had never really thought about before. The people of our vast

nation were neatly alphabetized files on my desk.

Because Chuck or Mary or Fred from

Coral Gables, Florida or Newark, New Jersey or Lafayette, Louisiana decided

that they had invented a better mousetrap, so to speak. They saved up money to

purchase a provisional patent for a year of protection against idea theft and a

chance to get their idea on a manufacturer’s desk. In their minds, a year was

plenty of time for them to strike it rich and sell their idea to Kraft,

AT&T, Tyco or Titleist.

When they saw this invention in

their mind, it was awash in a heavenly light. Who wouldn't want this idea? It was a minor inconvenience for Ted or William or Kelly to

quit drinking the Sam Adams and switch to Milwaukee’s Best or for Fillipe to make his kids eat macaroni and cheese dinners three times a week or for Bo to max out

his credit card. They were certain a company would want to buy their invention

from them.

The job seemed straightforward at

first. All I had to do was write about the client’s invention. That’s it. No

sales calls and very little filing. After the inventor doled out the money, I

received a form in a manila folder that described his or her “invention.” By

the end of week one, I came to realize this term was used loosely. These

people, they had no idea how this thing worked. Some of them hadn’t really

thought it through. They just had an epiphany on the toilet, or after a few

Long Island Iced Teas at happy hour, or a random brainstorming session before

the end of CSI: Miami. In the time it

took David Caruso to take off his sunglasses a few times and solve the crime

using a fleck of evidence from a soda can and a smudged fingerprint on a table

leg, the newly-christened inventor would have come up with an idea now known as

their invention. And that’s it. No building or testing or thinking required.

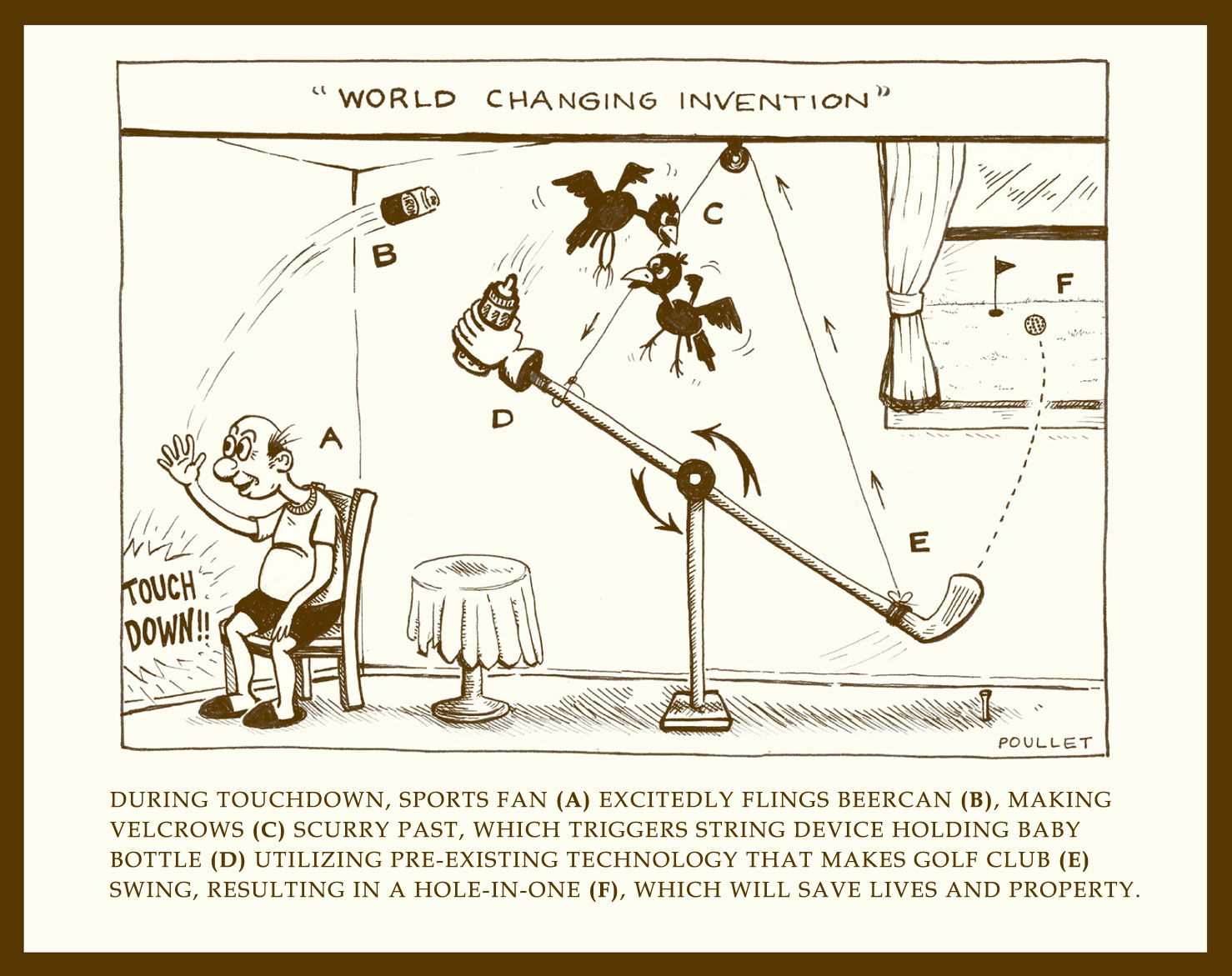

But, they couldn’t spell. They would

spell Velcro “VELCROW” —which would make me think that two birds would hold the

pieces of their invention together in their beaks. Which, sadly, was just as

conceivable as some of the ways these inventors thought their invention would

be assembled.

There was a space on the form for an

image. I was lucky if a picture was stapled to the paper, or if Kelly was an

elementary school art teacher, I could figure out what the heck she was

thinking when it came to her invention. But more often than not, the space was

filled with something that looked like it should be scribbled on the back of a

cocktail napkin. Important parts, such as VELCROW, would be labeled with an

arrow. Maybe.

So, they couldn’t spell, and they

couldn’t draw, but that the one thing these people could do was present their idea like it was an infomercial. In that

picture in their minds, the one where the invention is on a velvet pillow and

lit from the heavens, Chuck or Bo or Kelly is standing right next to it, making Vanna White gestures and smiling. Not only are they

going to be filthy, stinkin’ rich, they are going to

be the next Ron Popeil or Tony Little or George

Foreman. According to their form, their product will “SAVE LIVES AND

PROPERTY!!!!” all capital letters, four exclamation points. It is bigger,

better, brighter than the competition. Only they don’t always know how it will

work. It’s more of an idea than an invention. A concept, really.

It was my job to both encourage a

manufacturer to take these ideas seriously and present it in a way that the U.S.

Patent Office could understand so that the provisional patent, once filed,

would prevent someone from stealing their idea. I had some key words that I

relied on: convenient, utilizes, provides, features, more efficient, determined

upon manufacture, cost-effective, and, my favorite, the unit. As in, “the unit

utilizes pre-existing technology.” That was what I typed when the inventor had

no idea how it worked.

So, if you think about it, I was really creating the inventions. I

was taking a few sentence fragments almost illegibly scrawled on the paper form

provided by my employer, and turning them into a beautiful product that will

hold baby bottles, aid golfers while on the course, make windshield wipers

automatically turn on in the rain. I will provide society with a new bath

pillow, aquarium, reciprocating meat and bone saw. Thanks to me, when you drive

your big rig, you can exercise on an integrated weightlifting system, or easily

perform repairs with a step attached to the wheel. I will give you jeans with

holes cut out of the ass and gaudy plastic covers for your shutters that will

announce a birthday or wedding or show allegiance to your favorite sports team

(Go Steelers).

Months passed, and I continued to

slog through ever-growing piles of manila folders on my desk. It seemed like

everyone and their mother and their second cousin had an invention that was

going to save lives and property, all while raking in the money and enabling

them to quit their day jobs.

Everyone except people in Western

Pennsylvania. According to the forms, most inventors hailed from Florida or

California, with a few from the cornfields of the Midwest or the most humid

part of the Deep South. Here in Pittsburgh, we didn’t come up with inventions,

or at least we were too smart (or too poor) to need the services of an

invention company. The last time we invented something revolutionary was the Primanti Brothers sandwich (you know, put the French fries

and the coleslaw on the sandwich).

So, I ate Primanti sandwiches and drank Iron City and

watched Steelers games and began to wonder about working for the competition.

I had heard rumors that another

invention company in Pittsburgh made their employees wear lab coats. They

developed inventions in spaces specifically designed for the type of invention.

I imagined sitting in a rocking chair in a Goldilocks and the Three Bears-esque house, rocking back and forth while typing on a

laptop about some newfangled thing designed to hold pacifiers. I envisioned

Disney-colored break rooms and bathrooms in tree houses.

But instead, I took a new job

working for a museum fabrication company that specialized in the mounting of

dinosaur bones. Dinosaur bones were real. They could be touched. To everyone

except religious fanatics, they already exist. I got to use new words such as

disarticulate and metatarsal. I vacillated between the use of Tyrannosaurus rex, T rex and T.rex, instead of having to say hook-and-loop

adhesive fastener because Velcro is trademarked.

After I left, I heard that some of

the things I wrote about were actually bought by manufacturing agents. So, I

guess that when some guy on TV is yakking on in the middle of the night about

this product that chops and slices, fits in the glove compartment of your car,

is constructed from durable, waterproof plastic or other similar material and

makes you lose 20 pounds in a week, thereby saving lives and property, feel

free to thank me. Or just take me out for a Primanti sandwich.

Stephanie Brea has slung coffee, wrote

about inventions and worked for a company that built museum exhibits. This

means she likes her espresso doubled, is most likely responsible for some of

the products pitched on late night infomercials and can spell archaeopteryx

without the need for spell check. She is a part-time copy editor and

facilitates creative writing workshops for local schools and organizations. Her

work has been published in Pear Noir!, The Legendary, Nerve Cowboy and the Pittsburgh

City Paper.